October is #ADHDAwarenessMonth. As someone who was diagnosed with this neurodevelopmental disorder only recently, having lived with it unknowingly for over 50 years my life, it is now a very stark reality to me that the public understanding of this condition is woefully lacking and laced with misconceptions and false “facts”.

I know this because even after I was diagnosed, the information provided was scant at best and it was only after I made a conscious effort - not easy with ADHD as you will learn - did I start to have merely a basic understanding of how so much of my life has been dictated by this condition.

Here’s a quick fact to start: ADHD affects around 8% of the global population. Some kids have it but grow out of it. For the rest of us, it is a cradle-to-grave condition.

I will be writing more throughout the month about my personal struggles with this disorder, and how it impacts not only those of us with it, but also everyone around us; from loved ones and family, to friends and colleagues. I will talk about how medication helps - to a degree - but how the health system (in the US at least) fails us on so many levels, making receiving even the barest minimum of treatment a constant struggle.

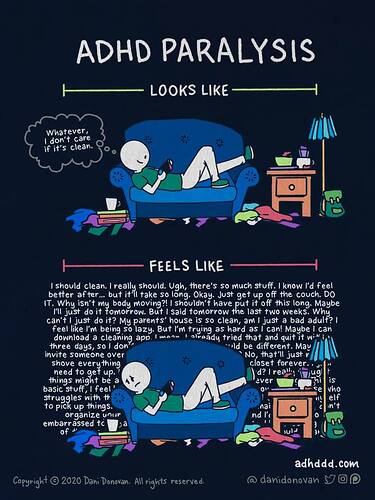

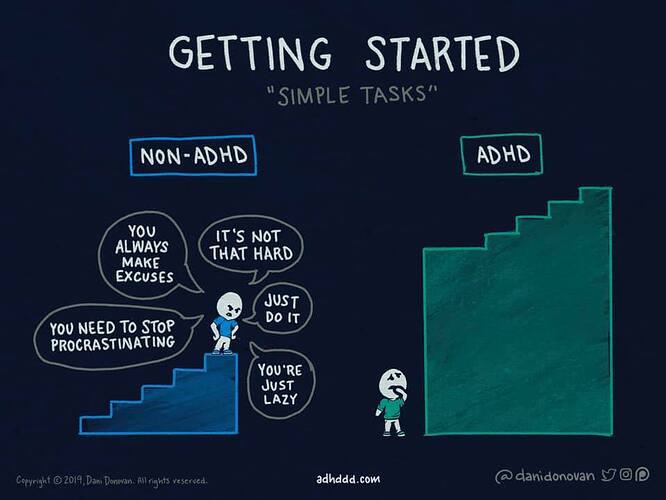

And I will write about how society doesn’t take ADHD seriously, seeing it more as a character flaw or failure of upbringing; which leads to anxiety, insecurity and depression…which society also sees as character flaws and failures of upbringing. These issues are exaggerated in those of us not diagnosed until adulthood and for those of us yet to be diagnosed.

I hope that you will follow along and gain a better understanding of this condition. Those of you who know me, may well get a better understanding of me, too. There may well be some of you who - like me - have been navigating life in a world not designed for those of us whose brains function differently, and have gone undiagnosed for whatever reason.

If you do nothing else, please just take away this: it is real and we can’t help it.

But I urge you to do at least a couple more things. Please read, like and share these posts. And please watch this 17-minute Ted Talk from Jessica Mccabe who, despite being diagnosed and treated from childhood, “failed at normal” but found her place in a society not built for her.