Perfectionism is another trait of ADHD, it seems. Nothing is ever finished until time has run out.

5. Undiagnosed in the Workforce

I did not have any clue what I wanted to do after leaving school. From the age of 13, my focus had been on the Air Force but, as I got older, that waned as a preference. I do not know if that was just me maturing and losing interest, or because of the crippling insecurities I had to fight through every day. College had never really held much interest for me (I would’ve been an even worse college student than I was high school), so into the workforce I go.

At least there’s no more homework, so it should be ok, right…?

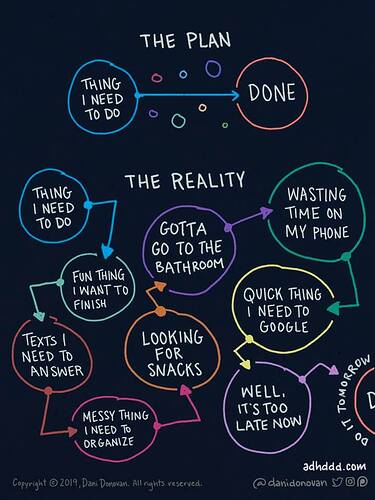

ADHDers are chronic procrastinators. It is the result of our neurodivergent brains seeking out the immediate dopamine reward of completing an interesting or urgent task, and so everything else just gets shoved down into the procrastination dungeon. However, contrary to what many think, we are fantastic at meeting deadlines.

We have an amazing ability to work quickly, we are creative, we can ingest piles of information really fast, we are great at engaging with new concepts and we are great problem solvers. The pressure of the time crunch delivers a powerful hit of dopamine when we’re up against the clock, so our brains are all-in on getting it done.

When I say great at meeting deadlines, I mean deadlines that come up today, like in an hour or in 5 minutes. Give us a deadline of tomorrow, next week or next month and you’re probably not going to be happy about when you get the response. Unless it was due yesterday, it’s likely to end up on the back burner and may never come forward again. Unintentionally, we will let a non-urgent task slip to the point it becomes urgent so that we get the neurotransmitter reward that otherwise would have been absent if the task had been completed at any other time.

We also have something called “hyperfocus”, which is the polar-opposite of attention “deficit”. When our brains latch onto something that is rewarding it with dopamine, it will shut out everything else and concentrate on that one task until it is done or the world ends. Nothing can pull us out of it; not time, thirst, hunger, other people, other tasks, a full bladder, atomic bombs or the Sun exploding. Many times I have emerged from hyperfocus to find myself alone in a darkened office, having not come up for air from a project for 8-10 hours.

So, in the workforce, we are going to excel at big, complex, gnarly and urgent projects and we will never, ever, ever remember to put the new cover sheet on our TPS reports. In fact, we’re probably not going to submit a TPS report in the first place. So, as crazy as I drove my teachers for “failing to achieve my potential”, I am going to burn up a whole bunch of bosses and colleagues going forward.

This also means we are generally excellent in crisis situations.

This is starting to hit close to home. Hmm.

Agreed. Although often they are of our own creation.

When a crisis hits, all the insecurity and self-doubt get wiped away and we leap into action like the dopamine junkies that we are. There is no problem in crossing the gaps on the motivation bridge, because the crisis just handed us a motivation jetpack.

6. Working Memory and Executive Function

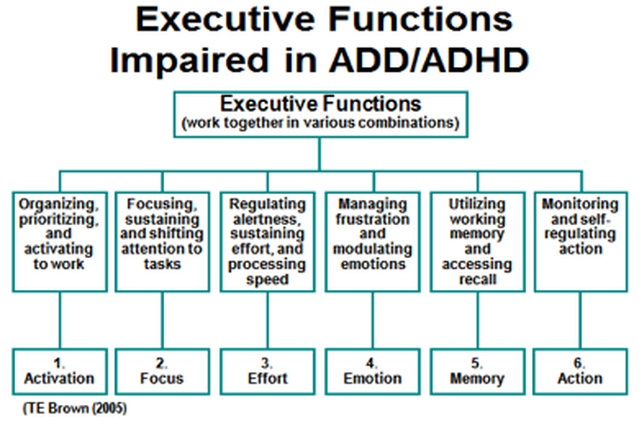

When it comes to memory, the human brain is a bit like a computer. It has long-term storage that is like your computer’s hard drive, which is compartmentalized into folders where it stores all your knowledge and memories. And it has “working” memory that is like your computer’s RAM, which it uses to intake new information and hold it until it is filed or discarded. Like RAM, information in working memory is overwritten by new information if it’s full, and the overwritten information is lost unless it had already been saved to the hard drive.

ADHD brains have less working memory than neurotypical brains. Information coming in is going to fill it up more quickly and thus overwrite what’s already there more quickly. This is exacerbated by the unintentional channel-surfing nature of our attention, in that we can easily find the channel switching on us before we’ve processed the contents of our working memory and what was there has been overwritten before we even knew anything about it. Poof…gone.

That’s why you can give an ADHDer a list of 5 things to do and they will forget at least 3 of those things almost immediately. If I had a dollar for every time I got up out of a chair and forgot where I was going before I’d even crossed the room, I could buy a new brain. It’s how we can go to the store for one thing, come back with 10 things, none of which are the thing we went there to get.

But, more than that, the ADHD brain has a deficit in its ability to manage executive functions. These are are the mental processes that enable us to plan, focus attention, remember instructions, juggle multiple tasks, control our impulses and manage our emotions. All of these things that are vital in navigating a world designed around the workings of a neurotypical brain are - without medication, therapy and training - extremely challenging for those with a neurodivergent brain.

To strain the computer analogy further - it’s not that we are missing an app or two, we have a whole different operating system. It’s like plugging a Mac into a Windows system and expecting it to work. Our brains have to be managed differently, which is not always easy when the world expects us to work one way and we work the other. It’s not that the Mac is stupid or broken, it’s just that it doesn’t work the same way that Windows does, so it looks broken to the Windows world.

When I started on ADHD meds, I was astonished that I could actually remember a chain of 4 or 5 things, like “ok, I took the trash out and then saw the rake and I put that in the garage and the hammer reminded me to pound down a few nails sticking up so that means I still need to put a new trash bag in.”

Unfortunately, those meds made he irritable, to put in mildly, so I had to go without.

7. How the World isn’t Helping

In the workplace, information is coming at you fast and furiously. People talk about multitasking, but that’s not really what most people are doing. They’re task-switching, being able to set aside the current task, do something else and pick up the original task where they left off. You’re writing an email, the phone rings, you answer it, action whatever comes from the call and return to your email. Modern workplace computer apps are designed specifically with this is mind.

But here is an area where the ADHD brain and they way the world works really come into conflict. When your attention is already as flighty as a kitten on cocaine, the slightest distraction can set you off on a cascade of shifting attention such that you may never get back to where you were. At least, not in any timeframe that a neurotypical person would consider appropriate.

Conversely, when we’re in hyperfocus, phone calls or emails or even walking up to us and talking directly at us may not even break through. Our brains have activated a cone of silence over us while it milks that sweet, sweet dopamine, and it will allow nothing to break in. Our two brain states - wildly unfocused or hyperfocused - simply do not work with the way our silicone overlords tell us we should. I do not consider this our problem; we didn’t design those systems and they weren’t designed with us in mind.

Writing shit down, making lists, is one very useful tool here. To-do lists, phone call lists, shopping lists, packing lists and on and on. I recently went away for 3 days, and I made a list of what to pack and a separate list of the things I needed to do as I left the house. The discipline to make lists is invaluable but hard for us, because our ADHD brain is telling us not to worry because we’ll remember and then switches channels on us before you wrote down the thing you just thought of.

Good lists take a lot of honing and expanding. They also have to be literal and broken down into individual component parts. No nebulous entries like “Pack”, because that runs the risk of having your brain abandon the task halfway through, and you have no idea where you are with it. The Notes app on my phone is probably the biggest, single productivity tool I’ve had.

For my youngest the list thing was apparent at a very young age.

For trips I would make a packing list. It would include everything.

Short sleeve shirts (4)

Long sleeve shirts (2)

Underwear (5)

Etc

If it was on the list, he packed it.

If toothpaste were on the list but toothbrush wasn’t, there wouldn’t be a toothbrush.

He usually was packed and ready before the rest of us.

So it worked.

But more than that when I gave him the list he would come back with the packing done, the items on list checked off, and a clear sense of pride in having completed the task completely and efficiently.

Seeing what that did for him still gets me.

I have greatly appreciated what Limey has written as we share many corresponding situations. I was diagnosed with ADHD and Asperger’s in my 40s after seeing a psychologist for depression. I might write more about that later. But what AFBD wrote also hit home in a way.

My dad figured out how to tie in my interest in sports to motivate me to do something I had no interest in. Initially he would make a list of chores and tell me no allowance until I had completed the tasks. Ha, I was 8 to 13 years old, money meant almost nothing to me, I would procrastinate. He then came up with the notion of timing me. He would make a big deal about how it would take him 20 minutes to mow the yard but if I could do it in 19 minutes, I would be the new record holder. That motivated me. I can’t vouch for the quality, seeing how I was in a hurry. Each time I mowed I was timed and I always tried to do it faster. Eventually I was damn near sprinting pushing that mower trying to beat my personal best.

When it came to math, I had no interest in those number things they wanted me to do. Then he started calling it Mathball and would have me figure out ERAs and batting averages, or yards per carry, points per game and such. Which helped a lot until algebra came along.

They didn’t call it ADHD back in the 60s. Most teachers just thought my lack of interest was because I was dumb but really I was just focused the birds I saw in the trees outside the classroom window or the way that cute girl’s ponytail would bounce with her every movement, or how the tile patterns on the floor would be cut to fit along the wall and in the corners, the trash can is almost full, or how cool The Beatles were. Important shit.

8. Time and the ADHD Tax

I try not to think how much money I have thrown away, or failed to collect, because of my ADHD. Just as the workplace is designed only with neurotypical brains in mind, the same is true of the financial world we all have to navigate.

Exhibit A: my current employer provides decent health insurance at a reasonable price. This comes with a healthcare points system that requires every covered adult to complete a series of healthcare-related tasks through the year. It’s all easily achievable…for a neurotypical brain. I haven’t accrued the necessary points this year, naturally, so next year I will be paying a “fine” on top of my insurance premiums. The fine will add up to more than $700 by the year’s end.

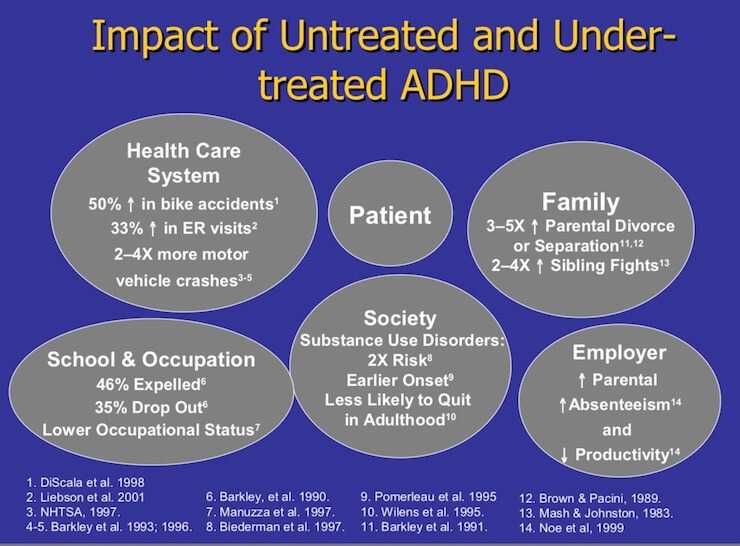

Bills have to be paid. Miss a loan payment and you get assessed a late fee and have your credit score dinged, which means the interest you pay on future borrowing is higher. Many with ADHD will end up in bankruptcy or foreclosure; their credit destroyed forever. Even if you avoid such extreme circumstances, the world will still end up charging you more or paying you less because you have ADHD than it would have if you didn’t.

Today we can pay all your bills online. But unless there is the option to schedule a recurring payment, the ease of paying still works against an ADHD brain. We have no concept of time. Well, that’s not strictly true. Time to us is either “Now” or “Not Now”. Making bill-paying so quick and easy online means that those tasks gets stamped “Not Now” and shoved down into the procrastination dungeon with all the other non-urgent tasks. So we can still fuck up and miss paying bills because they made it easy…for a neurotypical brain.

This trouble we have with perceiving time has broader impacts than just missing payment deadlines. We struggle to accurately predict how long things take to do. So if you ask us to do something right now, we will underestimate how long it will take us so - even though we may have completed it faster than someone else could’ve done it - we missed our target so you’ll still be mad. Now remember how we are carrying insecurities forward from childhood, think how we will feel when - after a job well done - we still received criticism because we said 30 minutes and it took an hour.

Similarly, set a deadline for down the road, and there is a good chance we will decide - wrongly - that we can get that done in “X” amount of time, so we don’t need to start that job until the deadline minus “X”. In this way, we queue tasks by a priority system based not on the importance of the job or even the importance of the person doing the asking, but based our own skewed sense time and our own interest level. We still need that dopamine hit, don’t forget, so the tasks that will trigger a brain reward go to the top of the pile, all other priorities rescinded.

This all drives people crazy and inevitably it will cost us in our careers and our relationships. That’s a tax infinitely worse than a fine on health insurance premiums.

We are convinced that my wife lost her first job, at least in part, due to her ADHD. She graduated college with honors and was more than qualified, but college did not prepare her for the time management challenges that lay ahead. Her boss at the time tried a lot of things to support her, but looking back those were treating the symptoms instead of the root cause. It’s easy to see now how she could have succeeded if we had only known what was going on and how to seek treatment for it. Since doing those things, she has not only gotten her career back on track but has been thriving.

I have a module already written up on my career ups and downs that I’m still not sure whether to post. The main takeaway is that I have been fired more often than I care to admit, and have gone through two protracted (6 months) periods of unemployment. I have no doubt that the outcomes in all these moments would have been better had I been aware of my condition and receiving treatment at the time.

Limey (and everyone else), thanks for this thread and your posts. As the parent of the ADHD teenager, I feel like I’ve made both every mistake and gained a lot of the insights described here. Reading through it in one consolidated place is incredibly revealing.

9. Emotional Control…Nope

The last major element of ADHD that I have yet to mention is the impulsivity; the inability to keep emotions in check. I do not think that am not too badly afflicted by this, but I cry at movies (sometimes in the wrong places) and at funerals - any funeral, even of people I didn’t know attended by people I don’t know. However, anyone who has ever ridden in a car with me, or played golf with me, or been within earshot when I am confronted with a malfunctioning piece of equipment may disagree about the level of my impulsivity and emotional control.

We also feel personal slights much harder than they are intended, which is an especially treacherous trait given that the very nature of ADHD means that we will have people griping at us pretty much 24/7. We are already likely to be riddled with anxiety and insecurity, so any rebuke or rejection however minor can ignite the entire box of fireworks.

Back in London, when I was being passed over for colleagues who I deemed to be less talented, I quit. I took another job instead, from which I was fired in less than 2 years. And so it has been for nearly 40 years; periods of success adorning a career that has lurched from bad decision to bad outcome, reinforcing my already overbearing insecurities and fueling the depression that has been ever-present since childhood.

Since I began treatment, I have found a position that I enjoy. I am able to work full time from home, which is something I have tried prior to treatment with disastrous results. I just passed my 3rd anniversary at this job, and the time has flown by.

But treatment is a constant struggle. My employer’s health insurance company dropped my long-term doctor, so I had to find a new one. The new doctor refused to prescribe the stimulant I have been taking, instead prescribing a non-stimulant alternative. Now the insurance company is refusing to cover the new medicine, so I am being asked to pay $1,000 out of pocket that won’t even contribute to my deductible.

10. Diagnosis and Treatment

I was attending couples counseling in an effort to save my second marriage (spoiler alert: nope). Part of the process was that we would have joint sessions and individual sessions with the counsellor. After the first joint session, my then-wife went for her individual session where the therapist started to ask her about my ADHD and how that was affecting the relationship. So obvious was my condition to her that it had not occurred to her that we didn’t know.

After that, I went to see my GP and was tested for the condition. Turned out I am ADHDAF. She prescribed a stimulant, and it was as game-changing as people describe; like putting on glasses for the first time or turning on noise-cancelling headphones. The blur of distractions just disappear, and you can function like a “normal” person.

The stimulant works to boost the level of neurological transmitters (e.g. dopamine) and brings them up to where a neurotypical brain lives naturally. This takes away the desperate scramble for stimulation that causes the ADHD brain to be unable to stay on topic. Without the dopamine gremlin channel surfing on your brain, focusing on any given task is possible.

Still, this is treating only the symptoms, and it is not an actual cure (there isn’t one). The pills don’t address the psychological damage that the condition has wrought and they’re only a temporary fix. Balancing the dosage to get you through the day is an imperfect art, the stimulant’s performance will naturally ebb and flow over time, and how it is prescribed and dispensed is the most ADHD unfriendly thing possible.

The stimulant is typically an amphetamine, which is a controlled substance. Consequently, you are only allowed a maximum of 30 days’ supply and are required to see your doctor every three months in order to get your next three 30-day batches of prescriptions set up. If you don’t collect your next 30-day supply within fews days of it becoming available, it is cancelled. Because a 90-day supply has to be issued as 3 separate 30-day prescriptions, sometimes the pharmacist will fill the 3rd one in error, which automatically cancels the first two.

All of this is a minefield for someone with ADHD. Between the pharmacy’s screw ups and my ADHD brain, I don’t think I went more than 2 months without my doctor having to reset the prescription, by which time I had probably run out and was more than likely going to fail to pick up the new one before the window closed and it was cancelled. So the necessary maintenance drug my condition requires is subject to one of the most artificially convoluted dispensing processes possible.

11. Treatment Catch-22

Stimulants work great when you remember to renew and collect your prescriptions and when nothing goes wrong in the ridiculous dispensing process and you have the balance right to get you through the day without the dosage becoming too low that your ADHD kicks back in and you forget to take a second pill. Whew!

As good as they are for most of us, the medication stops working as soon as we don’t have it in our system. So it’s still just a band aid on the problem. However, ADHD typically comes as a package deal with anxiety and depression, and that is much harder to deal with. Hopefully nowadays, early diagnosis of kids will spare them a lifetime of failing at school, failing at work and failing at home, that leaves us with self-esteem lower than whale shit. Sadly for the rest of us, these comorbidities are already baked in before we get diagnosed.

The insecurity and self-loathing you get from being told on a daily basis that you’re lazy or that you aren’t trying or that you don’t care leads to the “Imposter Syndrome”. This is such that, when anything is miraculously going well, you are convinced that you shouldn’t be here, that it’s not real and you don’t deserve any good that is coming from it. Ever been subject to gaslighting? Now imagine you’re being gaslit by your own brain. The voice telling you that up is down and light is dark is inside your own head.

The pills give you the ability to focus on tasks in the moment, but all of the psychological damage that has been wrought has to be addressed too, especially when the damage is deeper and more strongly rooted for those of us who are diagnosed later in life.

In my case, I was first spotted by a therapist who was working on my relationship, not my own mental health, so they took no further action on my condition. My doctor gave me pills, and told me to come back in three months. The pills help, as I explained before, but no one took the time to assess me for - or even mention - the classic comorbidities of anxiety and depression that accompany ADHD.

That these comorbidities can be especially pronounced in someone who has only been diagnosed as an adult, no one even mentioning this to me as an aside is a big miss. I had been flying blind my whole life and even though I now had glasses to help me see, no one had bothered to turn on the lights.

We need counseling not just for the past, but also for the future. We need to learn coping skills and best practices to manage our condition, and warning signs to avoid falling back into the pit. We need to understand our condition so that we can explain it to others (and to ourselves) so that we’re not - yet again - told that we’re lazy or not trying or that we don’t care.

As of time of writing, I am nearing the end of a three-month wait to see a specialist in the area of ADHD and associated depression. This is for an assessment to see if they will take me as a patient. There are limited options in this field and even fewer on my insurance plan, so fingers crossed. I did not see another therapist in Houston who is approved by my insurance company so, if they don’t take me, I’m faced with paying exorbitantly out of pocket, or traveling hundreds of miles for treatment - neither of which is likely to happen.

The Catch-22 of a condition such as ADHD - which has no outwardly physical manifestations and is so easily explained away as laziness - is that it’s invisible to everyone except experts, and those of us suffering with it will struggle to push for treatment…unless we are getting treatment already.

We need support and help the same way that a cancer patient needs a “chemo buddy”. Someone to help us help ourselves without judging our failings. Here is where the truly insidious aspects of ADHD get in the way, because so often we lose the people we need to help us because our ADHD burns them up.

This has all been very enlightening to me. When I was in Grad school for my Masters in Social Work back in 93, I had a classmate approach me to ask if I had ever been evaluated for adult ADHD. Her husband was a pediatrician who also saw adults with ADHD.

I told her I meet all the criteria but that I had been successfully managing it thus far and wasn’t interested in pursuing any medication at this time. What she was responding to was her frustration at my coping mechanism of turning every lecture class into a discussion class by asking questions and turn it into a discussion with the professor. (I also have very poor fine motor skills and mild dyslexia so taking notes was a problem).

I did well in Grad school. I have done well professionally. Pretty good relationally. My family has treated me with a great deal of grace, especially my wife who is extremely structured ( I joke that she makes a list about what she needs to put on a list). My kids laugh about the times I forgot to pick them up in elementary school.

But many times, I have been walking on the thin edge of failure. I self medicate with a bunch of caffeine. I struggle with focus. I procrastinate. I seek the adrenaline/dopamine hit of pulling things out of the fire. Sometimes I wonder if I am self sabotaging.

I have talked with my PCP before about medication but haven’t recently. I likely will bring it up again when I have my next visit.

It seems like self-sabotaging, and I have thought the same thing in the past, but it isn’t. It’s the dopamine gremlin needing to make everything a crisis to get the benefit from it. You’re actually trying to help yourself, not hurt yourself.

I would try the medicine and see if it helps you. It’s not addictive in the doses we need (you seem like you would need a lower-than-average dose too). So, if it doesn’t work for you or you simply don’t like it, you can drop it and go back to how you were coping before.